Zoning ordinances are restrictions on land use set by local governments. These may be use-based or they may regulate lot coverage, building height, or a variety of other characteristics. Inspectors can better serve their clients by learning how zoning laws affect construction in the areas in which they operate, although offering advice regarding zoning or variances is beyond the scope of a commercial property inspection, and inspectors may want to refer their clients to a local municipal representative if questions arise.

While the concept of zoning emerged from controls developed by European cities in the late 19th century, the first zoning ordinances in the U.S. were adopted by New York City in 1916 in response to the negative reaction to the intrusive shadow cast by the Equitable Life Assurance Building, considered the world’s first skyscraper at 38 stories and 538 feet tall. While other cities followed New York’s example, zoning ordinances remained contentious until they were upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court when a Euclid, Ohio, landowner unsuccessfully challenged them. This 1926 decision stated that zoning is constitutional, provided that it is designed to protect the public’s health, welfare, and safety.

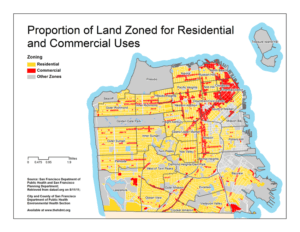

Zoning laws typically segregate land uses into three main categories: residential, commercial and industrial. Mixed-use zones allow the overlap of categories, which are commonly residential and commercial. Each category can have a number of sub-categories, such as where residential zones may be defined to allow or exclude sleeping units whose occupants are transient (such as motels and boarding houses) or permanent (such as apartment buildings and dormitories), as well as assisted-living communities, and various other types of multi-housing units. Commercial zoning usually has several categories that are dependent upon the business properties use and sometimes the number of business patrons and parking availability. Office building, restaurants, shopping centers, hotels, certain warehouses, apartment buildings, and vacant land that has potential to be developed into commercial property can all be zone as commercial. Nearly any kind of real estate besides single-family home and single-family lots can also be considered commercial real estate.

Proponents of zoning argue that its restrictions promote economic efficiency and protect property values by segregating incompatible uses, curbing over-development or interference with existing residents or businesses, and preserving the character of a community. Critics, however, are wary of the authority that zoning officials have, such as city councils that can limit the power of property owners to modify their own land.

Business owners may request that a variance is granted to allow for alterations to their property that would otherwise violate local zoning ordinances. Examples may include extending an addition beyond the setback line or erecting a fence that’s considered too high. Owners may have to persuasively argue to zoning boards that the alteration would prevent significant personal or financial difficulty and not threaten the safety or value of neighboring properties.

Fines incurred by violators of zoning ordinances are set by city and county governments, and they can be substantial. According to their website, Yuma County, Arizona, for instance, can issue fines of up to $750 per day for residential violations. Fines for exceptional cases can be in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, such as an Indianapolis landlord who was charged up to $300,000 in fines in January 2011. The city’s mayor commented that the fines “address unsafe, hazardous properties that present health and safety risks,” according to the newspaper Indystar.

To ensure that a project is abiding by the limits of a variance, property owners may want to hire a CCPIA inspector to inspect a project during construction or after it’s been completed. Inspectors, too, can diversify their knowledge base and better serve their clients by learning the subtleties of their local zoning laws. During a buyer’s inspection, for instance, an inspector may discover a zoning violation and impress upon their clients that they – not the previous owners who created the violation – may be responsible for its removal and any fines they may incur if they purchase the house. For added protection, buyers may want to ask sellers to add a clause to the sales contract that guarantees that any alterations they made to the property complied with zoning ordinances and that they are responsible for any future fines caused by the modifications.

In summary, zoning ordinances are restrictions on the use and construction of land and real estate, and inspectors can help their clients with a basic understanding of their local zoning laws while emphasizing that such advice is beyond the scope of an inspection.